I am discovering that there’s some powerful psychology going on when you get a new car.

Playing into this for me is that my old car was wearing out, and was getting difficult to drive, plus the change from manual to automatic.

This means the new car seems like a breeze to drive.

The “new car smell” is real, and somehow makes it seem pleasurable to sit in the driver’s seat.

The extra features – even on this model which was as cheap as I could buy in the size I wanted – are (I’m guessing) designed to appeal, to make you want to be in the car (and thus to drive it).

Some designers have identified cupholders specifically as desirable, with some perhaps unlikely explanations:

Rapaille says women love cup holders because — and this is really what he told her — cup holders mean coffee, and coffee means safety, because of the memories we all have of our mothers preparing coffee with breakfast.

And this: Anthony Prozzi, design manager for Ford in Michigan, explains that “part of a designers job is to play psychologist, anthropologist and sociologist, and knowing those things helps you read consumers and know what puts a smile on their faces.”

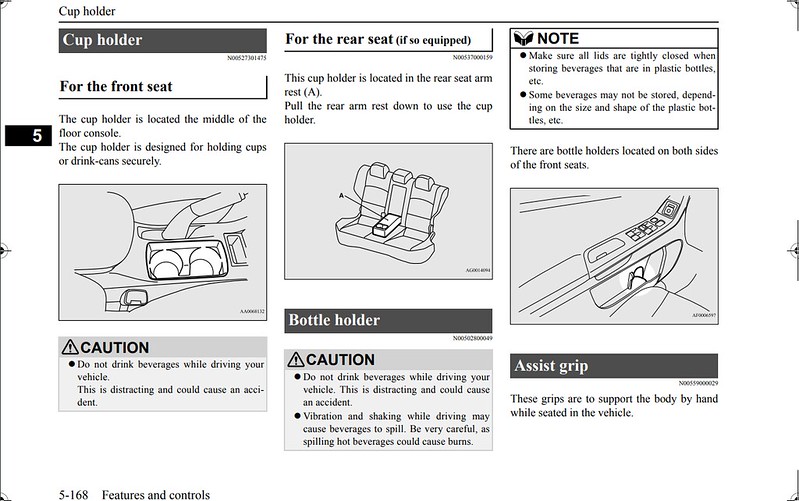

My new car has a spot to put a bottle in the door (like my old car did) plus cupholders in the centre between the front two seats. So I can have two drinks within easy reach if I want… while the manual warns you not to actually use them while driving. Plus it’s got a spot for a packet of tissues, in case I have a spill.

I suppose car manufacturers have been at this game for a long time. You’ve bought their product for thousands of dollars – they want you to feel good about it, so that in time you’ll want to upgrade to another one.

The net result is that – even for someone like me, who understands the consequences of driving, and doesn’t like driving – I feel like I want to drive it.

I’d never drive it to work. Parking is too expensive, traffic is too soul-destroying, and (usually) the train is too good.

But it’s tempting to drive it other places where PT options are fewer – and I can understand why some people would be tempted to drive every day, even into horrible traffic. Combined with (Australian) governments who keep building big roads, even though it doesn’t solve congestion (it expands it), the desire to drive is powerful.

Just get in, turn the key and go. It’s so easy. Mostly the noise, air quality and traffic impacts are Somebody Else’s Problem. The motorist doesn’t pay for them; society does.

Governments are complicit in this, especially in Australia, where they build ever more roads as cities get bigger – despite this being not how the world’s biggest cities solve their mobility problems.

So the desire to drive is powerful.

Fighting back

All this means that those of us who believe in the importance of solving those impacts through alternative transport modes have to make sure that they improve enough to fight back. If everybody who could afford to and was able to was on the roads, it’d be a disaster.

Perhaps to an extent cars are self-defeating. The more crowded the roads become, the better the alternatives look.

I also associate the car with first escapes, driving nowhere in particular in the middle of the night with a friend, movement being a goal in its own right. … Countless trips have been made by car since then, and we (still) own a small car today. However, trains became our favorite transport mode a long time ago, and as a family, we nowadays associate highways with congestion and stress, places to avoid. — Stefan Gossling

Ultimately to fight back against the car, the other options need to improve.

Gossling again: There are powerful interests at work to psychologically engineer car addiction—addicts, conveniently, never question their behavior. Other insights pertain to the role of cars with regard to emotions, sociality, sex and gender, speed, authority, and death. We need to understand these interrelationships to unlock the possibility of alternative transport futures.

Can public transport improve?

One could focus on the psychological aspects of public transport, but what about the basics – making the system easy and pleasant to use?

Cleanliness, crowding, information, security and easy to use ticketing all come into it. But seamless connections and cutting waiting times to reduce door-to-door journey times are fundamental requirements.

It would be easy enough to despair. Progress is so damn slow.

Most suburban buses are still running to frequencies from cuts 25 years ago. The last tranche of the better quality orbital Smartbus routes were implemented in 2010, almost a decade ago.

Trams have seen capacity expansion (big trams replacing smaller trams) but few route extensions, and remain slow due to a lack of progress on traffic priority.

The noises about public transport expansion are positive, but the actual progress isn’t.

Particularly frustrating is that literally billions are being spent on new rail tunnels to fix peak hour (great!) but most suburban train lines continue to run only every 20 minutes at most times of day, 30 minutes evenings. There are still gaps of 40 minutes on some lines on Sunday mornings.

A few have improved, but on most lines at most times they are much the same now as they have been for 30 years.

Let’s face it, with some exceptions, outside peak, most of the public transport system remains pathetically infrequent and slow, especially for a city of nearly five million people — despite increasing all-day demand.

Really, it’s no surprise that most people continue to drive.

The car industry is doing its best to coax us in, and on the other side, every signal from authorities, every pathetic half-baked public transport upgrade, every poorly-programmed pedestrian crossing, every non-existent bike path tells people to drive.

To curb the many problems of the car, they have to do better.

12 replies on “The desire to drive, and how we must counter it”

“some people would be tempted to drive [to work] every day”.

According to ABS 2016 Census data for Victoria, 12.6% of commuters use public transport and 68.3% get to work by car.

That’s a lot of temptation!

I loathe commuting to work by car. 30 minute walk to a station, 30 minute trip into the CBD. Same coming home. Sorted for about $10.

It also gives me an hour to read … well it used to, as everyone around me seems to yak on the phone these days. So now it is podcasts and talking books.

Yesterday Metro had an altered timetable from Cranbourne to Dandenong (shuttles only all day, running every 20 minutes). This was promoted on the website/app as beginning three days later, until some people on Twitter began asking questions. Anyone who asked why this was not communicated properly in advance was ignored. Metro doesn’t seem to get that most reasonable people understand why there are disruptions when they are genuine, but poor communications about planned works aren’t good enough. Maybe somebody yesterday tried the train for the first time in a while yesterday, and won’t again after this experience.

Apart from one case where I had to drive to physically be able to go to work in outer western Sydney, I haven’t been tempted all that much – courtesy of surprisingly bad roads in the outer suburbs, rude drivers, and high insurance premiums and other costs. (I swear, Sydney roads has the worst: narrow roads from Japanese cities with numerous and crazy drivers from American cities.)

At least I can sleep/read on most of my train rides to work/shopping/music rehearsals, and they are generally reliable enough. Although, Uber Pool (or even just carpooling with a friend) is starting to be a thing now.

What are you thoughts on a future where cars are self-driving?

@David, it’ll probably happen eventually, but nowhere near as fast as the boosters are predicting. The technology isn’t exactly covering itself in glory, and significant problems continue to plague it.

When it does happen though, regulators will need to get serious about things like road use charging, especially if vehicles have largely switched to electric power, bypassing petrol taxes. The last thing society needs is driverless cars dropping off their masters then driving home again (eg 4 trips for each daily commute, with an average occupancy of 0.5) or worse.

This is something I have noticed in my personal psychology.

I like to explore. Walking is a slow way to explore. Cycling is better. Driving is better still. Motorcyclying is the best. (It feels like you are flying and you have a much better field of view.)

Your comment “I also associate the car with first escapes, driving nowhere in particular in the middle of the night with a friend, movement being a goal in its own right.” made me realise this.

Enjoyed the blog.

@Daniel, I’m with you in that I think it will take a lot longer than excitable types in the media and tech industries are touting. I was more curious as to what you think the impact of self-driving cars will be on the appeal of public transport systems – they will remove a major downside of private transport as it exists today (the inability to do much other than focus on the road while travelling) while retaining the benefits (freedom to travel where and when one likes and not having to be stuck in close quarters with strangers).

@David, a lot of the appeal of public transport in big cities is due to space-efficiency.

Travelling around in a self-driving car won’t solve traffic congestion (even vehicles bunching together will only go so far, and vehicles making trips by themselves may counter any advantage) so in busy city centres, I expect public transport is likely to remain competitive – even once self-driving cars become affordable/the norm.

In my opinion is finishing off legacy projects that should have been completed a long time ago aka north east link, airport rail, east west link, metro 1. But eventually these giant legacy projects will be behind us and we can then focus on actually thinking about how can we move to better public transport system. Why cant it be as good as London someday, with rail also going from east to west someday also. It be great if more big ideas were thought of post metro 2. If we have 800k-1 million people in 2028 (20% more then now), we can surely think of bolder public transport projects to do rather than the same ideas that never got done.

Very interesting article. I believe the is a factor of attachment and excitement when you buy a new car that makes you want to use it even more than an old car.

[…] I’m liking the car. The only thing I don’t like is the rear spoiler. I think it looks a tad silly, I doubt it has great aerodynamic benefits, and it partially blocks the view from the rear vision mirror and when doing a left shoulder check. […]